Credentials and Other Official Stuff

- B.A. in English and Secondary Education

- M.A. & Ph.D. in Rhetoric and Composition/Writing Studies

- 16 years teaching writing at the university with students from freshman to graduate level

- 5 years of experience directing a university writing center

- 6 years of experience as a freelance editor

Getting Schooled: My Writing Journey

A woman who writes has power, and a woman with power is feared. — Gloria E. Anzaldúa

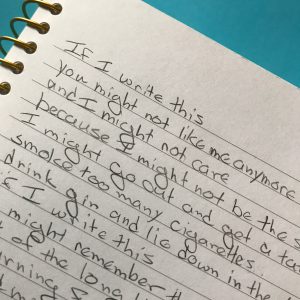

My name is Carrie and I am a writer. It has taken me decades to feel comfortable defining myself in those terms again. Like happens to so many young writers, school stripped me of the joy and passion I had for writing. Often that school trauma comes in the form of red ink—papers returned with endless grammar, punctuation, and sentence structure corrections that convince students that they can’t write. All that attention on the surface of the writing tells students ” your ideas don’t matter” because the teacher fills up the page with so much red ink that there is no space left to see them. Those students become adults who fear writing, believe they are bad at it, and don’t see the point anyway because their ideas don’t matter. I was one of those lucky students to whom the basic mechanics of writing came easily, so I avoided the red ink. I was encouraged with praise and good grades. Teachers engaged with my ideas and writing became a way for me to feel smart. But as I grew older I slowly learned that attention to your ideas comes with consequences as well as benefits. Popular, conventional ideas garner praise. Ideas that disturb the status quo come with backlash because those who benefit from the system are not going to give up their privilege without a fight.

In sixth grade I learned that the unschooled use of words strike fear into those desperate to maintain control over even the smallest of fiefdoms. Three friends and I started an unauthorized class newspaper. After two issues we were shut down by the principal who found the idea of four preteens writing about school events without adult supervision a potential threat to her power. The articles we wrote were completely benign. The threat was in our ability to reach an audience of our peers without any help or supervision from those in authority. We controlled the means of production and could use it for our own ends.

My journalism got a similar reception in high school where I was an op-ed columnist for the official school newspaper. Each month when my column came out I was called down to the principal’s office to “discuss” my writing and why it was “troubling.” My column about the condition of the school bathrooms was so troubling the superintendent came down to view them for himself. The adrenaline rush from that victory was exhilarating. My writing had forced action and change. But calling out those in authority was dangerous, even at the high school level. They couldn’t stop me from writing, but they could take away something I cared deeply about at that time—my graduation honor cords. I knew I had earned them, but my name was wiped from the list, and on graduation day when the cords were passed out I went away empty handed. I had been schooled.

In college a friend and I coauthored a letter to the administration asking them to address the unequal treatment given to female students. In the letter we wrote that if our concerns were not addressed we would take our grievances to the local newspaper where they would be read by the local community, parents, and students. This was a conservative, Christian school that did not take kindly to two upstart students infiltrating their squeaky clean public image. We were told the only solution to the unequal treatment of women on campus was not to grant women the same privileges as the male students, but to take privileges away from the men so they would be subject to the same rules as the women. We were told no one would be happy with us if that was the result of our letter. We would be social outcasts. And of course, the upper administration would have our letter and our names. The stakes were higher this time. These were not people who would stop at taking away ceremonial honors on graduation day. They would take away graduation altogether.

So we took our letter and went back to our dorm. We ate our words, and I have held on to their bitter taste to this day. It is a reminder that writing operates within complex power structures at the personal, local, national, and global levels. Writing has power when it dares to confront the status quo, but that comes with consequences—retaliation—which creates fear. The result is a voice that can find no words and retreats further and further into silence.

Graduate school was another disciplinary exercise. The research and writing that received praise and awards extended accepted theories and methodologies

But one can only remain silent if their survival and the survival of those they love remains unthreatened. Conditions in my country are no longer ones that ensure survival of any but the most privileged. I could no longer lie to myself and pretend silence is an ethical choice, so I picked up my began to write. And I invite you to do the same.

I will not have my life narrowed down. I will not bow down to somebody else’s whim or to someone else’s ignorance. —bell hooks

If you are a writer or aspiring writer, I would love to help you realize your goals.

WRITING COACHING

EDITING