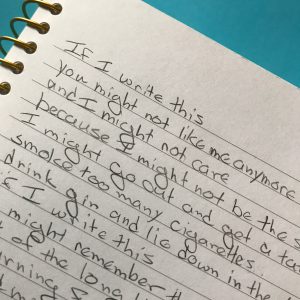

Several months ago I took Isabel Abbott’s Unapologetic Writing class. I was trying to unlearn all the negative lessons I had internalized about what truths it was appropriate to speak and write. I wrote a lot and kept it all to myself. Most of what I produced was process writing—writing to help me work through the hurt and the anger and the fear. One piece emerged as a manifesto of sorts for my unapology—my taking back of apologies past and writing what needs to be written. It’s not a graceful poem, but it’s jarringly true, and at this moment that’s what counts.

If I write this

you might not like me anymore

and I might not care

because I might not be the same.

I might go out and get a tattoo

smoke too many cigarettes

drink gin and lie down in the street naked

if I write this

I might remember the way they grabbed me

out of the long line of girls returning from gym class

pulled me behind the stage and held me down

on a table there to hold props.

Till I screamed and they ran.

I might remember my clothes

thrown at me as he ordered me to get out

his laughter as he said no on would want me now.

I might remember I am broken, angry,

not fit for the PTA and garden parties.

if I write this

I might go out in the rain and dig in the dirt

ripping up roots of deep buried weeds

waiting to rise up in place of all I have planted with my soft hands.

If I write this

I will know that feeling

the one that seeps in at night,

that surrounds me in the shower like tiptoeing fingers of doom

that makes me mutter “shut up” to the empty room.

If I write this

I can’t stuff it at the bottom of the hamper with the bloody sheets and come to dinner.

If I write this

you will have to know with me because I won’t remember to be silent anymore.