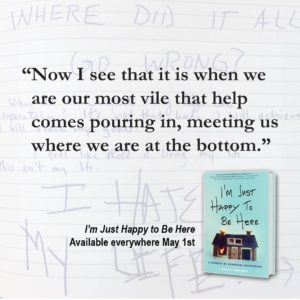

My friend and writing mentor Janelle Hanchett’s memoir, I’m Just happy to Be Here, debuted today. I had the honor to be part of a select group of early readers, and if you follow me on social media, you have seen my posts about what a beautiful, heartbreaking, funny, and inspiring story it is. It takes you into the depths of motherhood and addiction in a way that anyone who has experienced a dark night of the soul can understand. And isn’t that all of us, really?

I discovered Janelle’s writing in 2015 when a friend shared one of her blog posts on Facebook. I don’t even remember which post it was because I immediately started reading the whole blog. She wrote about motherhood and social expectations and politics in a way that was sarcastic, outraged, and ernest all at once. She outed herself as imperfect, a misfit, and invited all the other misfit mothers to join her. When I found out she was offering an online writing class I knew it was meant for me. but I was only half right. It was meant for me and seven other amazing women who became fiercely loyal friends and writers in progress.

After a year of working together online and joking about the magical face-to-face writing retreat we were going to have someday, we decided to make it a reality. So Janelle set to work finding us the perfect location—a funky, well-worn 1960s commune turned retreat center in Pescadero, California. This was not a resort in Tahiti, where all the spiritual white women go on retreat these days. This was a misfit cabin in the woods perfect for a gang of misfit writers. We gathered in the yurt in the morning to talk about writing, spent the afternoons actually writing in the living room, and listened to each other read around the campfire at night. It was there that I first heard Janelle read from her book. When she was finished, we were all silently crying in the dark because we knew this book would be everything we love about Janelle’s writing and everything we hope for in our own—real, raw, and offering real human connection.

Janelle’s writing is brave because she knows life is too short to give any fucks about propriety and other outward signs of white, middle class adulting. There is only time for honesty and kindness, and love—for helping each other up each and every time we fall. Near the end of the book, when she is finally in recovery and staying sober, she reflects on the importance of telling her story. In the scene she is visiting a home for alcoholic mothers and explains,

I tell them what I did and how I recovered, because I want them to see that the water they need to wash themselves clean flows always and immediately to the lowest possible places. And I know that God, to me, is that kind of love.

This was the moment that brought me back to that campfire and the way I felt afterward as we all walked back up the hill to the retreat house to go to bed. This book is bedtime story for grownups—not a fairy tale where good triumphs over evil, but a story of how a flawed, messy human (as we all are) gets a chance to try again, a shot at redemption.

Reading this book has overlapped with my spring gardening rituals of pruning and planting and weeding. Every year I go back to the same trouble spots, the places where despite my diligent weeding and watering plants refuse to grow, seeds refuse to sprout. I have a place in my flower garden where only weeds will take hold. Each spring, I dig out the weeds and plant a new sort of flower, hoping this variety will finally be the one that can stand up to the weeds. I have been doing this for 10 years now, and each time I go out to plant in that spot my husband reminds me of that old saying: the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results. But this is where God finds us—at our most desperate, on our knees in the garden trying again to make something grow. God is there with lowliest of us who continue to make the same mistakes, continuing to love us, tend to us, like a patch of poor soil where only weeds will grow.

The wisdom in Janelle’s book is that we are all already redeemed, already worthy of love. We just have to step into the water and let it wash over us.

About a month ago I went to hear a friend speak at Fort Collins Startup Week, a conference by and for local entrepreneurs. Her presentation on how to sell your services without feeling like a smarmy jackass (not her actual title) was affirming and encouraging. I left feeling confident and ready to tackle the day. So why 10 minutes later when I pulled up in front of my house did I stay slouched down inside my parked car like a getaway driver looking for cover? I sat there scrolling through Facebook on my phone like it was my damned job.

About a month ago I went to hear a friend speak at Fort Collins Startup Week, a conference by and for local entrepreneurs. Her presentation on how to sell your services without feeling like a smarmy jackass (not her actual title) was affirming and encouraging. I left feeling confident and ready to tackle the day. So why 10 minutes later when I pulled up in front of my house did I stay slouched down inside my parked car like a getaway driver looking for cover? I sat there scrolling through Facebook on my phone like it was my damned job. My writing practice has gone off the rails and getting back on track has been an enormous struggle. I am tired, and angry, and sad. Every day I wake up, look at my phone and greet the day’s tragedy or injustice. A bombing. A shooting. Another sexual predator exposed. Another assault on our democracy by Congress and this monstrous presidency. It’s exhausting. And I’m white, straight, cisgendered, and middle class and thus reasonably sheltered from the fallout. I’m one of the lucky ones.

My writing practice has gone off the rails and getting back on track has been an enormous struggle. I am tired, and angry, and sad. Every day I wake up, look at my phone and greet the day’s tragedy or injustice. A bombing. A shooting. Another sexual predator exposed. Another assault on our democracy by Congress and this monstrous presidency. It’s exhausting. And I’m white, straight, cisgendered, and middle class and thus reasonably sheltered from the fallout. I’m one of the lucky ones.