It’s been almost a year and a half since I began my obsession with Marie Howe‘s poetry. She has a way of revealing the emotional meaning of everyday moments and objects by focusing on their materiality. She doesn’t turn away from the ordinary in favor of the philosophical because the meaning is in the thing itself. The description on the back cover of her book The Kingdom of Ordinary Time sums up this idea:

Hurrying through errands, attending a dying mother, helping her child down the playground slide, the speaker in in these poems wonders: What is the difference between the self and the soul? The secular and the sacred? Where is the kingdom of heaven? And how does one live in Ordinary Time—during those apparently unmiraculous periods of everyday trouble and joy.

In the Catholic Church, Ordinary Time is the part of the liturgical calendar not part of the Christmas or Easter season. In other words, Ordinary Time is most of the time. And it is not a time of insignificance where our spiritual, emotional, and intellectual life stops or slows down. Nor is it simply a time of preparation for the holidays, the special times. It is where we live and love and die through the folding of laundry and cleaning of sinks. It is where we come to know God and ourselves. Whenever I need reminding of this, I listen to Howe read her poem, “The Gate.”

I am participating in Andrea Scher’s Brave Blogging course, and one of the lessons included an interview with poet Maya Stein, whose 10-Line Tuesday poems reminded me of a writing practice Howe assigns to her students. Both require the poet to place a singular focus on an object or moment without turning away. Stein uses the limits of only ten lines to maintain her focus. Howe requires her students to come to each class with one sentence describing something they saw or otherwise experienced through the senses, and they must write that sentence without the use of metaphor—they must focus on the thing itself, they cannot turn away, they cannot intellectualize or explain. Only after they master this practice of describing things can they use these things as metaphors for something else.

This writing practice of staying with the thing itself is much like meditation. Meditation asks the practitioner to stay with whatever feelings arise without trying to explain them because the act of explaining is a form of distancing, of easing the the intensity of both pain and joy.

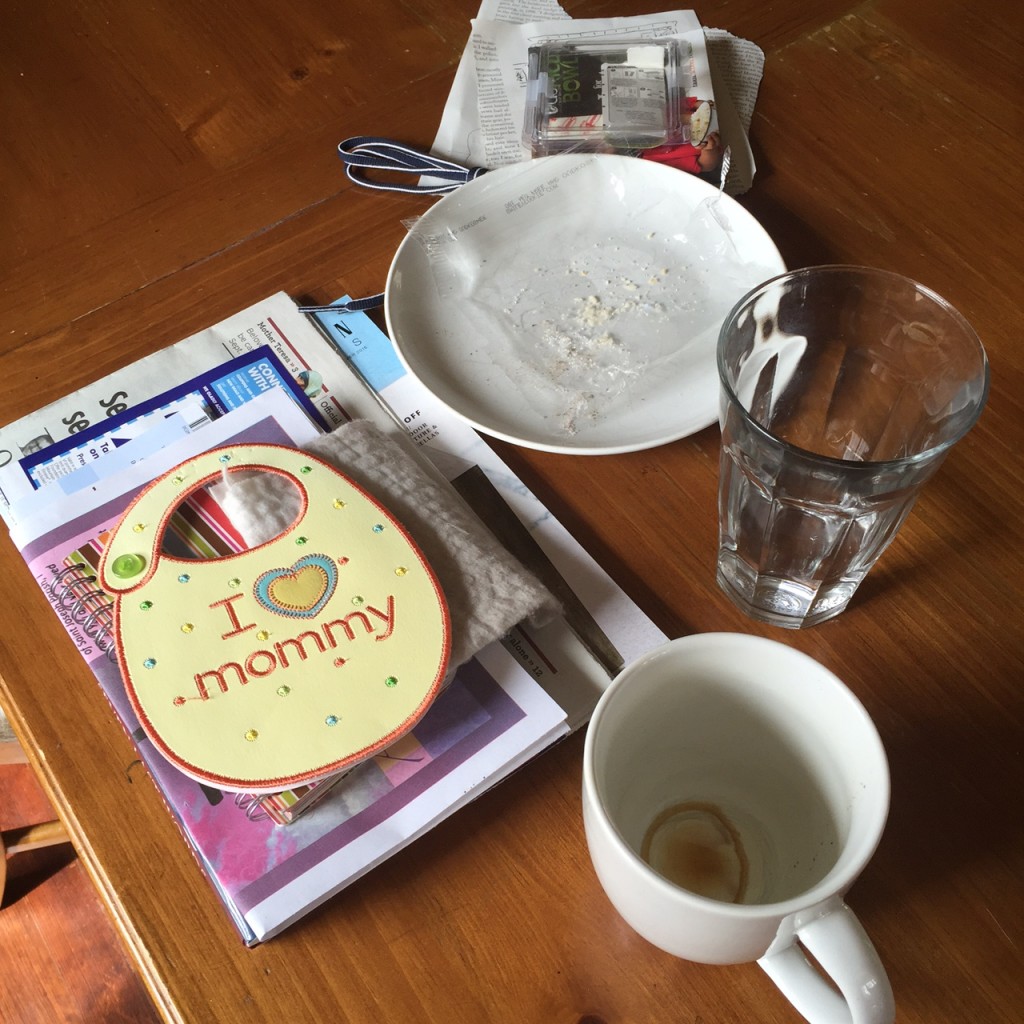

On May 16, the Church will enter its long stretch of Ordinary Time that lasts until the Christmas season begins in November. While I love Easter and the rebirth of earth and spirit that happens in Spring, it is all for naught if we can’t figure out how to live in the ordinary time of Summer and Fall, of growth and harvest, because if we can’t we starve. So I am preparing for ordinary time by following Howe’s assignment to write one sentence each day describing something from my ordinary life. My goal is to work up to a point where I can reflect on the materiality of my life half as beautifully as Stein does in an inch of vinegar:

You’re saving it, apparently, for a salad you keep forgetting to make.

In the bathroom’s mirrored cabinet, a flick of nail polish left at the bottom

of a small glass jar. There’s a rumpled bag in the garage holding a clutch of dirt

that will likely not root the plant you’ve yet to purchase from the garden store.

These leavings, these leftovers, this clinging to the maybe useful – the house

is full of both optimism and neglect, a store of Lilliputian portions

incapable of meeting your large and shifting demands. The coupons

you are so scrupulously stockpiling. The last dregs of living room paint.

A spool of thread down to its final three loops. A candle with less than an hour left

you hold onto, nevertheless, certain you will need that light somewhere.

In the meantime, I’ll continue training myself to be fully present with the ordinary.